Professional tennis’s anti-doping programme took a significant step forward in 2013 by conducting more out-of-competition tests as part of its introduction of biological passports. However, inconsistencies and omissions remain in the programme – how was Del Potro not tested out-of-competition? And for comparison, the number of tests per player significantly lags that of professional road cycling. Report card therefore: a solid B (or mention bien) but plenty more to do.

1) INTRODUCTION

A few days ago, the ITF (the International Tennis Federation) published statistics from tennis’s anti-doping programme for 2013. Even if the announcement, press release and data tables did not pass you by, by the time you actually got to look at the data more likely than not you would be none the wiser. This is not helpful, especially when you consider the focus, impact and controversies surrounding the suspensions last year of Marin Cilic and Viktor Troicki (which this post does not discuss).

This post therefore will answer 4 questions:

- In 2013, who did (and did not) get tested?

- What type of testing took place?

- How does this compare year on year?

- How does the type and frequency of testing compare with other sports?

2) THE SUCCESSES

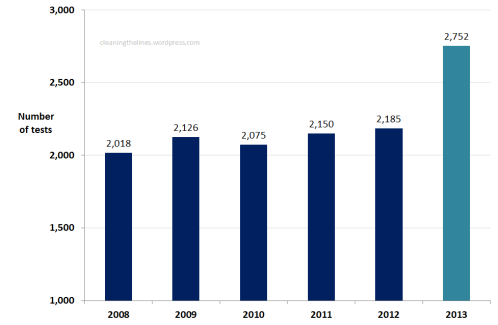

- The number of tests has increased. The ITF administered 2,752 tests in 2013, a 26 per cent increase against 2012. 784 separate players were tested. (Compare to 2010 when 666 players were tested.) Some players may also have been tested by their national anti-doping authorities.

Total number of ITF-administered tests 2008-2013

- The biggest reason for the increase against 2012 is the dramatic increase in the number of out-of-competition blood tests: from 63 in 2012 to 449 in 2013 (a rise of over 600 per cent). This is not accidental as it matches the introduction of athlete biological passports by the Tennis Anti-Doping Programme Working Group (comprised of the ITF, WTA, ATP and grand slams). This requires a corresponding increase in out-of-competition blood tests (as opposed to in-competition tests).

- Biological passports record anti-doping test results for a player over time and are considered by WADA, the international organisation overseeing anti-doping activity, to be an effective way of detecting potential doping activities. (See glossary below, if required.)

- Easy to conduct in-competition tests outnumber out-of-competition tests in a ratio of about 3.5:1 (2,159 in-competition tests vs 593 out-of-competition tests).

Out-of-competition tests (blood tests, urine tests, total tests) 2008-2013

- The top 50 singles players from both ATP and WTA tours were all tested at least once, either in-competition or out-of-competition. Only a handful of players from the ATP or WTA top 100 were not tested at all.

- The ITF’s statistics offer significant transparency by publishing the names of all players on which it conducted tests, and whether those tests were conducted in-competition or out-of-competition. However, the type of test (blood, urine) is not provided for each player.

3) THE ISSUES

- Out-of-competition testing in 2013 was negligible for players outside the ATP/WTA Top 50. On the ATP Tour, approximately 227 of the 307 out-of-competition tests in 2013 (74%) were conducted on those ranked within the singles top 50 at year end 2012. That figure is 239 tests (of 286, 84%) on the WTA Tour. [See footnote 1 below]

Out-of-competition testing by ATP/WTA Tour and by Rank 2013

- Issues of consistency remain. Despite focusing on players in the top 50, 4 ATP top 20 players (at year end in 2012) were not tested out-of-competition at all by the ITF in 2013. Remarkably, that group included Juan Martin Del Potro who qualified for the World Tour Finals in 2013. Also in that group were Tipsarevic, Monaco, and Dolgopolov. On the WTA Tour Jelena Jankovic (YE 2012 ranked 22) and Varvara Lepchenko (21) were the highest ranked players not to be tested out-of-competition.

- Comparing ITF statistics to those produced by the UCI for men’s professional road cyclists, tennis still has a way to go. The leading 513 professional road cyclists on the UCI WorldTour were tested on average 11.7 times in 2012 (this report, pages 13-16). According to the ITF data, the 500 tennis players (male and female) who were tested the most in 2013 were tested on average 4.7 times; the majority of those players were only tested between 1 and 3 times. Admittedly, this does not take into account any additional testing conducted by national anti-doping bodies (for example USADA in the US).

I’m not addressing here whether it is desirable or appropriate for tennis players to be tested as much as cyclists. That’s a question for others. However, it is clear that though the Tennis Anti-Doping Programme is on the right track, the programme also requires some enlargement, particularly for those outside the top 50.

*** End

Footnote

[1] There is an assumption here. The ITF-published data showing the number of tests per player groups the number of tests in three groups: 1-3 tests; 4-6 tests, 7+ tests. For the purposes of the above calculation, I made the assumption that a player with 1-3 tests was tested twice, a player with 4-6 tests was tested 5 times, and a player with 7+ tests was tested 7 times.

GLOSSARY

There is plenty of technical information on the website of WADA, the international organisation that leads anti-doping efforts. Brief lay definitions of some of the types of tests and procedures are set out below.

In-competition tests refer to tests carried out during competition, for example during an ATP or WTA tournament.

Out of competition tests refer to tests conducted at any other time. Out of competition tests are considered by WADA to be “the most effective” means of detection and deterrence of doping due to being conducted “anytime, anywhere and without notice to athletes”.

Urine tests are the most widely used anti-doping tests (see WADA 2012 Anti-Doping Testing Figures Report). Urine tests are inexpensive and considered to be a reliable test for the presence of steroids, stimulants and substances such as Erythropoietin (EPO).

Blood tests are more expensive. Typically they are used to detect substances such as Human Growth Hormone (HGH).

Biological passports monitor certain biological variables of an athlete or player over time. According to WADA, discrepancies in the variables can “indirectly reveal the effect of doping, as opposed to the traditional direct detection of doping by analytical doping controls”.

Featured image: credit Reuters.