Monday saw the publication of the ITF’s anti-doping testing statistics for 2016. Tennis’s anti-doping programme has been the subject of criticism in recent years, in most detail recently by an investigation by ESPN’s Outside the Lines (OTL) in October 2016. The OTL investigation made 3 main points: 1) that historically tennis’s anti-doping programme was unsophisticated in its reliance on in-competition testing (as opposed to out-of-competition testing); 2) that tennis makes sparing use of sophisticated but expensive testing methods for detecting performance-enhancing substances such as synthetic testosterone; and 3) that not every sample is tested for EPO and human growth hormone (HGH).

However, as conceded by the investigation these are mostly historical points: tennis follows WADA’s guidelines for the rate of EPO testing samples (1 in 10 samples); out-of-competition testing has increased; the biological passport was introduced in 2013; and the ITF’s anti-doping budget in 2016 was USD 4 million, double its level from 2013. Stuart Miller, head of the anti-doping programme, estimated it would cost around USD 1.2 million to USD 1.6 million – only an additional 20% in budget – to test each sample for EPO and HGH.

Data from the ITF’s 2016 anti-doping programme

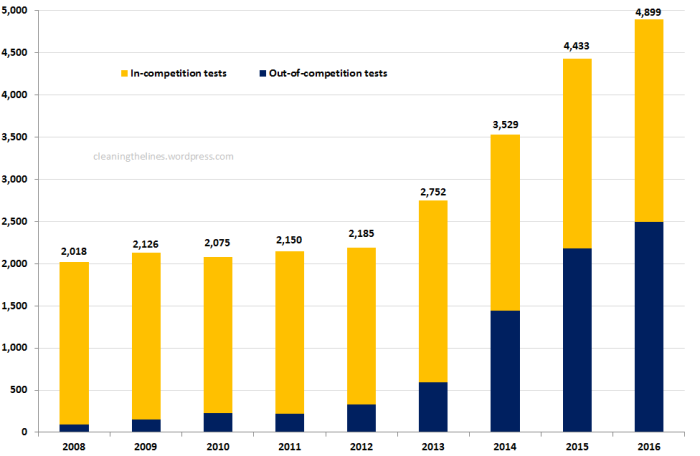

Analysis of the ITF’s anti-doping statistics for 2016 confirms that the direction of travel is positive. Firstly, 4,899 drug tests were conducted, an 11% increase on 2015, more than any year to date and more than double the number from as recently as 2012. 1,080 players were tested, again the most in any one year to date.

ITF Anti-doping Programme 2008-2016; in-competition and out-of-competition tests (raw data source: ITF)

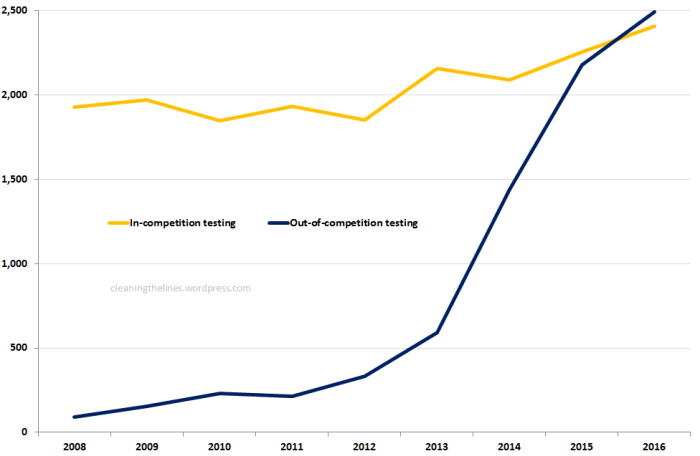

As can be seen from the chart above, the testing includes both in-competition testing as well as out-of-competition testing; and the increase in recent years has come overwhelming from an increase in out-of-competition tests (and specifically blood tests). Out-of-competition testing (both urine and blood) accounted for just 1 in 7 tests in 2012; this year for the first time, out-of-competition testing was responsible for more tests (2,492) than in-competition testing (2,407).

ITF Anti-doping Programme; in-competition and out-of-competition tests by year (raw data source: ITF)

It is worth noting that players may also be tested by their national anti-doping authority (e.g. USADA for the likes Serena Williams or Jack Sock): these numbers are not included in the ITF’s statistics.

Transparency

Where the programme excels is its transparency: the ITF publishes the names of players, and the number and type of tests administered (in-competition, out-of-competition).

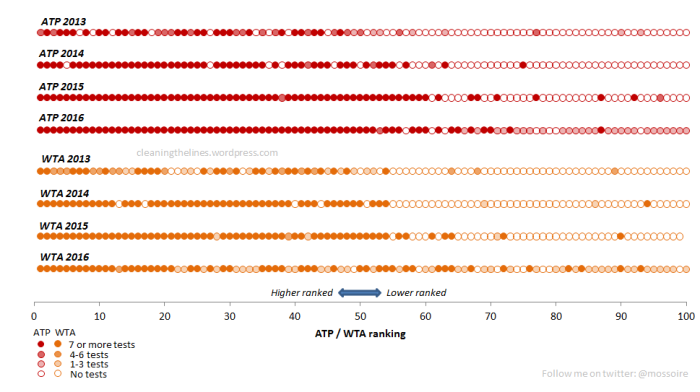

Accordingly, I have analysed the number of out-of-competition tests for ATP and WTA players ranked in the top 100 over the last 4 years [see footnote 1]. What this shows – see chart below – is that more players are being tested out-of-competition than ever before [see footnote 2]. Whereas in 2013 on both tours it was really only the top 40 who were being tested at least 7 times outside of competition, and there remained large swathes of top 100 players untested out-of-competition, recent years have seen steady progress to the extent that 2016 saw a total of only 16 players from the ATP and WTA tour top 100s not being tested out-of-competition.

Out-of-competition testing 2013-2016 – ATP / WTA Top 100 (raw data source: ITF)

Gaps remain, of course, and it is to be hoped that an interim goal for the ITF is for all players in the top 100 to be tested at least 7 times each year out-of-competition. As noted in a similar post this time last year that analysed the 2015 anti-doping programme, tournament winners on the main ATP tour can come from any rank within the top 100 (and even outside it – Florian Mayer was ranked 192 when he won Halle, coming back from injury) and safeguarding the reputation of the sport – and the sponsorship and increasing testing television revenues that come with it – is of course paramount.

Footnotes:

[1] For tests in 2013-2106, the ranking I have used is the ranking of each player from 31 December of the previous year. For example in 2016 chart above, the WTA world number 13 as at 31 December 2015, Victoria Azarenka, was tested 4-6 times out-of-competition in 2014.

[2] There is an assumption here. The ITF-published data showing the number of tests per player groups the number of tests in three groups: 1-3 tests; 4-6 tests, 7+ tests. For the purposes of the above calculation, I made the assumption that a player with 1-3 tests was tested twice, a player with 4-6 tests was tested 5 times, and a player with 7+ tests was tested 7 times.